In the long, profound history of Chinese calligraphy, there are numerous notable father-and-son calligraphers. The “Two Wangs,” for instance, Wang Xizhi (AD 303-361), dubbed as “Sage of Calligraphy,” and his youngest son Wang Xianzhi (AD 344-386) are arguably the greatest exponents of all time in Chinese history.

While the father was a master of all forms of Chinese calligraphy, especially xingshu (the semi-cursive script), the son’s most celebrated accomplishment is his invention of xingcao (the running-cursive script), a combination featuring both the cursive and running scripts.

Wang Xizhi created a technique named yibishu, or one-stoke writing, which laces together several characters into a single stroke.

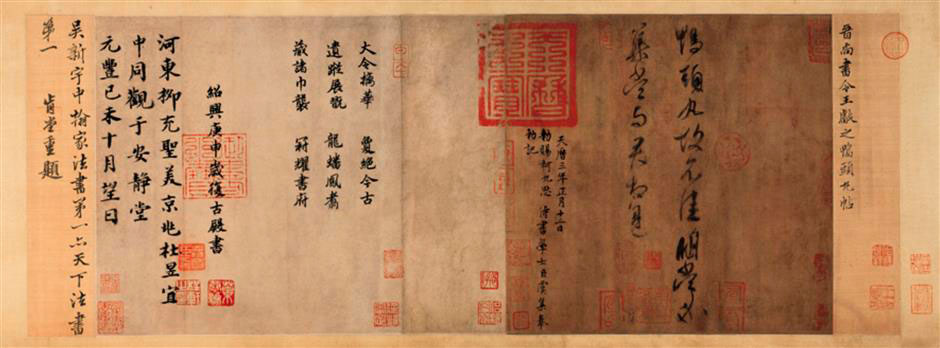

One of the most prominent works of this method is the “Yatouwan Tie,” or “Duck-head Bolus Note.” Its rubbing version is featured in the 10th volume of the “Chunhuage Tie” — the only collection of works by several distinguished calligraphers living before the Song Dynasty (AD 960-1279) that has survived over 1,000 years.

The calligraphy on the silk scroll, 26.1 centimeters long and 26.9 centimeters wide, demonstrates a short note of 15 Chinese characters the master wrote to his friend.

The text literally means “I took the duck-head bolus but I don’t think it’s as potent as some people thought. When we meet up tomorrow I would like to know your opinion.”

So what exactly is the so-called “duck-head bolus?” It comes from the culture of health-keeping practices which prevailed in the Wei and Jin periods (AD 220-420), and focuses on the cultivation of life.

During that time of considerable political turmoil and wars, noble people increasingly lived a secluded and cloistered life in an attempt to acquire the substance of life through the medium of body and bodily practices.

They indulged in Chinese medicine studies every day and gathered for developing effective health-keeping techniques from time to time in the hope of creating alimentary bolus that helps achieve longevity.

The duck-head bolus, as a type of traditional Chinese medicine, was favored by the nobles.

Considered to have a function of diuresis and reducing swelling, the pharmaceutical preparation was recorded in revolutionary medical books like Wang Tao’s “Waitai Miyao,” or “Medical Secrets of an Official Library” in the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907) and Li Shizhen’s “Compendium of Materia Medica” in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Many believed the medicine could boost health and self-cultivation and took it as a life-saver, while others believed it was a placebo and didn’t improve their physical conditions.

After taking the medicine, Wang Xizhi reckoned it was ineffective and thus created the legendary work.

The piece de résistance, collected by numerous emperors during the Song, Yuan (1271-1368) and Ming dynasties, was beloved by Emperor Shenzong of Ming. Recorded history documented that the emperor was fond of practicing calligraphy since childhood and took the “Yatouwan Tie” as a model to imitate.

It was not until after the foundation of the People’s Republic of China that the priceless script was exhibited to the public.

Ye Gongchuo (1881-1968), a renowned artist, scholar and collector with an expressive and straight-forward personality, devoted his life to collecting various relics and protecting ancient China’s cultural heritage. The most prestigious work in his collection is the long lost “Yatouwan Tie.”

Xu Senyu, director of the former Shanghai Committee of Cultural Relics Management, heard Ye intended to sell the script so his nephews could receive tertiary education. He turned to Xie Zhiliu, a famed connoisseur and friend of Ye, to see if the master could sell the work to Shanghai Museum.

Although heartbroken to sell the cherished collection, Ye was touched by Xie and the committee’s effort to protect the note. However, the invaluable “Yatouwan Tie” had never been priced and even the best connoisseur could not figure out its exact worth.

A Chinese idiom suddenly came into Ye’s mind — one word worth a thousand in gold (yizi qianjin), which is applied in praise of a piece of writing or calligraphy to show that each character is perfect and each word is highly valued.

Finally, the 15-character classic was sold for 15,000 yuan (US$2,295 today) during the 1950s to the Shanghai Museum.

As Wang Xizhi is to Chinese calligraphy as Michelangelo is to sculpture or Shakespeare to literature, Wang Xianzhi inherited his father’s talent for art and calligraphy. Until the Tang Dynasty, his influence and reputation rivaled and even surpassed that of his father.

A great calligraphic work would never be a simple repeating of a word but a composition with eternal beauty in variation.

After more than 1,000 years, the public can appreciate the immortal charm in Xizhi’s acclaimed “Yatouwan Tie.”

Source: SHINE