On the far west of the “Yangxin Dian,” or Hall of Mental Cultivation, in the Imperial Palace in Beijing, there is a side room called “Sanxi Tang,” or the Hall of Three Rarities. The room acted as Emperor Qianlong’s (1711-99) study at one time and housed three masterpieces of Chinese calligraphy — Wang Xizhi’s “Timely Clearing After Snowfall,” his son Wang Xianzhi’s “Mid-autumn Manuscript” and his nephew Wang Xun’s “A Letter to Boyuan.”

The trio, known as “Three Rarities Treasure,” were generally considered to be among the most precious remnants in the history of Chinese calligraphy.

Wang Xizhi, known as the “Sage of Calligraphy,” was also a politician of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (AD 317-420) and a master of all forms of Chinese calligraphy — especially the running script.

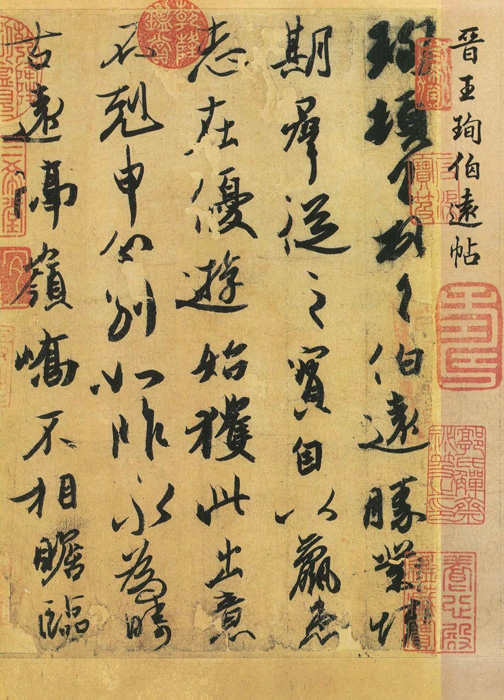

Written in a running-regular script, Wang Xizhi’s “Clearing After Snowfall” is a short letter containing only 28 Chinese characters in four lines. He wrote the letter to a friend after a snowfall.

“Clearing After Snowfall” is regarded as a running script masterpiece, second only to the “Preface to the Collection of Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion,” which is Wang Xizhi’s most noted work. It influenced many masters of posterity, such as Li Yong, who was a Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907) calligrapher, and Zhao Mengfu, who was a scholar, painter and calligrapher of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368).

Emperor Qianlong admired the “Three Rarities’” work so much that he sealed and wrote over 70 inscriptions on it and praised it as a “masterpiece of all time.” Yet, most experts don’t believe it is an original work. They say it is a Tang Dynasty copy. Unfortunately, none of Wang Xizhi’s original handwriting has survived.

Although the work is a copy, it retains its original nature — round, forceful and elegant. With a history of over 1,300 years, the national treasure now hangs in the Palace Museum in Taipei. The other two treasures of the “Three Rarities” are held by the Palace Museum in Beijing.

After the 1911 Revolution, which overthrew China’s last imperial dynasty and established the Republic of China, Puyi, who was the last emperor of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), was forced into abdication in 1912.

He and his imperial family initially remained in the Forbidden City and got a large sum of money from the government but it was still not enough to furnish their lavish lifestyle. To gain more money, the former emperor asked people to smuggle the imperial collections and sell them.

Consort Jin, a concubine of Emperor Guangxu (1871-1909), had her eye on the “Three Rarities.” However, she dared not to sell Wangi Xizhi’s “Clearing After Snowfall” because it would be too noticeable so she decided to smuggle out his “Mid-autumn Manuscript” and Wang Xun’s “A Letter to Boyuan.”

Wang Xianzhi, the youngest son of Wang Xizhi, inherited his father’s talent for the art of calligraphy.

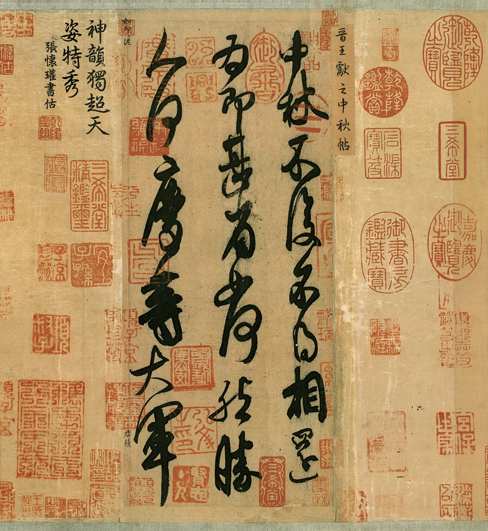

The calligraphic masterpiece “Mid-autumn Manuscript,” containing 22 Chinese characters in three lines, is believed to be an incomplete copy of a Wang Xianzhi’s work.

Made of bamboo, the paper was impossible to produce in the Eastern Jin Dynasty, as it didn’t appear until the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). Besides, the smooth strokes indicate that the brush used was soft. A brush made in the Eastern Jin Dynasty had a stiff center, therefore it cannot achieve the same effect.

Research reveals Mi Fu, a Chinese painter, poet and calligrapher of the Song Dynasty, copied the “Mid-autumn Manuscript.” The calligraphic work features many scholars’ inscriptions, including the Ming Dynasty’s (1368-1644) Dong Qichang and an Emperor Qianlong painting.

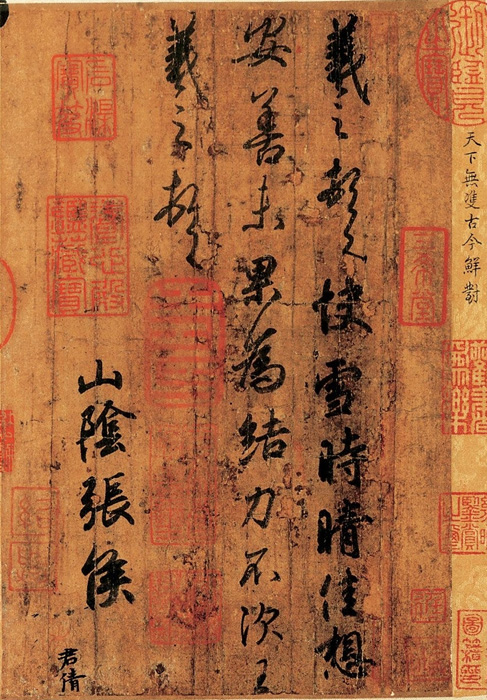

Wang Xun was also from the prominent Wang family. His work “A Letter to Boyuan” is regarded as the only authentic work of calligraphy from the Eastern Jin Dynasty. It ranks fourth in “the world’s top ten cursive script works.”

Instead of reaching out to big dealers, Consort Jin sold the “Mid-autumn Manuscript” and the “A Letter to Boyuan” to a small antique shop called “Pingu Zhai.”

Guo Baochang, who was the bookkeeper of Yuan Shikai, head of the Republic of China, purchased both of them.

Guo once invited Ma Heng, who was then curator of the Palace Museum, for a meal at his home in 1932. Guo showed the two treasures to Ma, who failed in his attempt to bring them to the Palace Museum.

In 1949, the two treasures appeared in Taiwan. Guo Baochang’s son Guo Zhaojun wanted to sell them to the Palace Museum in Taipei. However, the museum had a small budget and couldn’t afford them. Two years later Guo Zhaojun placed the treasures in a British bank in Hong Kong to get collateral. But when he returned to collect them Guo couldn’t afford to get them out.

Guo Zhaojun told his friend Xu Bojiao, who was a manager of a bank and a well-known collector, he had sold them to foreigners. Xu reported this to his father Xu Senyu, who was the director of the Shanghai Cultural Relics Management Committee, and Zheng Zhenduo, the head of the Cultural Relic Bureau. When former Premiere Zhou Enlai discovered the news he squeezed funds for the protection of cultural relics from China’s financial budget and paid for the “Mid-autumn Manuscript” and the “A Letter to Boyuan.”

Source: Shine